calvary building history

Calvary's west facade

Calvary's west facade

Calvary United Methodist Church - originally Calvary Methodist Episcopal Church - is an excellent example of a turn-of-the- century American Protestant church. In plan it reflects contemporary architectural philosophy which sought to give Protestant churches an auditorium-like open character, based on triangular of semicircular plans with converging rather than parallel lines of sight. Here the architects exploited to the fullest their wedge-shaped site.

The placement of the chapel on axis behind the sanctuary was also a common feature of this plan type in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The exterior of the church was treated as a freely-interpreted English parish church of the fourteenth century–although it was clearly influenced by turn of the century compositional ideas. Instead of taking the various parts of the building–the sanctuary, chapel, tower and office block–and expressing them with the detached volumes and shapes that Victorian planning called for, they were drawn together into a simple bold shape under a broad spread of roof. Built of granite with limestone trim, the interior of the church is notable for its decoration, including the two windows of the sanctuary, and its very well-preserved woodwork.

The church, although built between 1906 and 1907, derives from a design made ten years earlier. Immediately after the congregation was incorporated in 1895, a simple wooden chapel was erected to serve until a more imposing church could be built. The congregation followed the rapid pace of growth of West Philadelphia, and in 1897 the architectural firm of Dull & Peterson was chosen to design the new church.(1) John Dull (1859-1949) was a prominent Philadelphia architect who had worked with such important architects as T. P. Chandler and the Wilson Brothers. Presumably he was selected because of his experience in church design; among the ecclesiastical structures he built were the German Evangelical Church on Clearfield Street, the Swedish Lutheran Church on McKean Street and the Congregation Ruben Synagogue on South. 6th Street.(2) Dull is best remembered as one of the founders of Drexel University’s architecture department. He was also a very talented watercolorist.

Dull & Peterson completed their plans by June 6, 1897 when they were discussed in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Building Guide. They proposed to erect the church in two phases: a two story stone chapel with attached community rooms would first be built at the rear of the site on Baltimore Avenue; within a few years the sanctuary and tower could be added. Construction was already underway by February 8, 1898 when the Philadelphia Inquirer commented approvingly on the new church (p. 12) and the completed structure was dedicated on October 8, 1898 (see Figure 1).

The chapel served the congregation until early 1904 when the new minister, Dr. Albert E. Piper, decided that the church now needed its sanctuary. Accordingly John Dull (who had since lost his partner Peterson) was summoned to complete his original plan. He spent the early months of the year preparing the drawings which were discussed in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Building Guide (January 20 and February 17, 1904). Dull drew on his rendering skills to make an attractive wash drawing of the proposed church, showing a flattering view of the Baltimore Avenue flank with a picturesque silhouette of spires and gables. On March 9 the drawing graced the cover of the church’s “Ninth Anniversary and Jubilee Rally Program: 1895-1904” (see Figure 2). But even before the contracts were advertised for bids, Dull was discharged as architect for reasons that remain unclear. Perhaps his 1897 scheme was now viewed as hopelessly out of date. It is also possible that Dull was discredited because of structural problems in the already built chapel (problems that eventually led to its demolition.) At any rate, new architects were summoned in the fall.

New York architect William R. Brown was already preparing the plans in September (Builders Guide, Sept. 14, 1904) but he soon engaged the firm of Gillespie and Carrel to serve as associate architects. Henry Clay Carrel (1869-1915) was a New York architect with considerable experience in hotel design.(3) His partner, George Curtis Gillespie (active c. 1890 to c. 1920), had a more technical practice, including such New York buildings as the India Wharf Brewing Company (1899) and Weirs Warehouse (1900).(4) On January 259 1905, the plans were advanced enough for contractors to begin bidding (Builders Guide). Nonetheless, construction was delayed for nearly a year-possibly because of the problems associated with Dull & Peterson’s chapel building. The cornerstone was not laid until April 14, 1906 and work progressed throughout the summer. On November 24, 1907 the completed church was dedicated.

The placement of the chapel on axis behind the sanctuary was also a common feature of this plan type in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The exterior of the church was treated as a freely-interpreted English parish church of the fourteenth century–although it was clearly influenced by turn of the century compositional ideas. Instead of taking the various parts of the building–the sanctuary, chapel, tower and office block–and expressing them with the detached volumes and shapes that Victorian planning called for, they were drawn together into a simple bold shape under a broad spread of roof. Built of granite with limestone trim, the interior of the church is notable for its decoration, including the two windows of the sanctuary, and its very well-preserved woodwork.

The church, although built between 1906 and 1907, derives from a design made ten years earlier. Immediately after the congregation was incorporated in 1895, a simple wooden chapel was erected to serve until a more imposing church could be built. The congregation followed the rapid pace of growth of West Philadelphia, and in 1897 the architectural firm of Dull & Peterson was chosen to design the new church.(1) John Dull (1859-1949) was a prominent Philadelphia architect who had worked with such important architects as T. P. Chandler and the Wilson Brothers. Presumably he was selected because of his experience in church design; among the ecclesiastical structures he built were the German Evangelical Church on Clearfield Street, the Swedish Lutheran Church on McKean Street and the Congregation Ruben Synagogue on South. 6th Street.(2) Dull is best remembered as one of the founders of Drexel University’s architecture department. He was also a very talented watercolorist.

Dull & Peterson completed their plans by June 6, 1897 when they were discussed in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Building Guide. They proposed to erect the church in two phases: a two story stone chapel with attached community rooms would first be built at the rear of the site on Baltimore Avenue; within a few years the sanctuary and tower could be added. Construction was already underway by February 8, 1898 when the Philadelphia Inquirer commented approvingly on the new church (p. 12) and the completed structure was dedicated on October 8, 1898 (see Figure 1).

The chapel served the congregation until early 1904 when the new minister, Dr. Albert E. Piper, decided that the church now needed its sanctuary. Accordingly John Dull (who had since lost his partner Peterson) was summoned to complete his original plan. He spent the early months of the year preparing the drawings which were discussed in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Building Guide (January 20 and February 17, 1904). Dull drew on his rendering skills to make an attractive wash drawing of the proposed church, showing a flattering view of the Baltimore Avenue flank with a picturesque silhouette of spires and gables. On March 9 the drawing graced the cover of the church’s “Ninth Anniversary and Jubilee Rally Program: 1895-1904” (see Figure 2). But even before the contracts were advertised for bids, Dull was discharged as architect for reasons that remain unclear. Perhaps his 1897 scheme was now viewed as hopelessly out of date. It is also possible that Dull was discredited because of structural problems in the already built chapel (problems that eventually led to its demolition.) At any rate, new architects were summoned in the fall.

New York architect William R. Brown was already preparing the plans in September (Builders Guide, Sept. 14, 1904) but he soon engaged the firm of Gillespie and Carrel to serve as associate architects. Henry Clay Carrel (1869-1915) was a New York architect with considerable experience in hotel design.(3) His partner, George Curtis Gillespie (active c. 1890 to c. 1920), had a more technical practice, including such New York buildings as the India Wharf Brewing Company (1899) and Weirs Warehouse (1900).(4) On January 259 1905, the plans were advanced enough for contractors to begin bidding (Builders Guide). Nonetheless, construction was delayed for nearly a year-possibly because of the problems associated with Dull & Peterson’s chapel building. The cornerstone was not laid until April 14, 1906 and work progressed throughout the summer. On November 24, 1907 the completed church was dedicated.

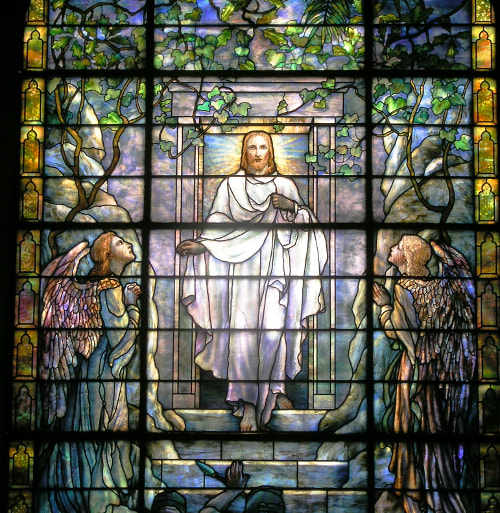

Central detail of Tiffany Resurrection window.

Central detail of Tiffany Resurrection window.

Brown and Gillespie & Carrel completely revised Dull’s original scheme. His design for the corner tower was preserved–down to the taller corner spirelet – but nearly everything else was altered. Most significantly, Dull’s plans for the sanctuary were abandoned; he had called for two flanks of buildings – a chapel and office wing on Baltimore Avenue and a nave wing on 48th Street, an intersection that would be marked with a corner tower.

Such a rambling asymmetrical composition reflected the Victorian design practice in which Dull had been trained. Brown decided not to place the sanctuary parallel to 48th street but instead created a symmetrical and much bolder shape: a wedge shaped auditorium whose long axis would bisect the site between the two streets. This was not only a more dramatic use for the awkward site; it also corresponded more completely with late nineteenth century Protestant church building philosophy, which had come to favor the triangular auditorium-type plan. The church sanctuary occupied the center of the lots with the chapel located on axis behind it while the wings fronting Baltimore Avenue and 48th Streets contained Sunday school play rooms, kitchen and dining facilities and the church offices.

Such a rambling asymmetrical composition reflected the Victorian design practice in which Dull had been trained. Brown decided not to place the sanctuary parallel to 48th street but instead created a symmetrical and much bolder shape: a wedge shaped auditorium whose long axis would bisect the site between the two streets. This was not only a more dramatic use for the awkward site; it also corresponded more completely with late nineteenth century Protestant church building philosophy, which had come to favor the triangular auditorium-type plan. The church sanctuary occupied the center of the lots with the chapel located on axis behind it while the wings fronting Baltimore Avenue and 48th Streets contained Sunday school play rooms, kitchen and dining facilities and the church offices.

Structural problems afflicted the church within a year of its completion. In the summer of 1908 the church was struck by lightning and the stonework of the tower damaged. Contractor Thomas Shinn received $500 to “replace stone on tower and repair roof” (Building Permit 5344; August 17, 1908). No significant work appears to have occurred for over forty years, although the church was damaged in the winter 1946/1947 by a windstorm (see insurance correspondence, Calvary Church archives). Ironically, the church tower was again struck by lighting in the summer of 1952. Contractor F. B. Davis and Sons estimated the cost to “repair lighting damage [and erect] scaffolding and masonry work in connection with church steeples” to be $4000 (Building Permit 5455; August 14, 1952–also see 1953 permit 4613). It may be in connection with this work that the steel clamps were inserted to secure the upper gable face of the Baltimore Avenue facade. The only other change of note seems to have occurred in the 1960s when the openwork spire that capped the small tourette on South 48th Street was removed.

This report was researched and prepared by Michael Lewis of Clio Group, Inc. for Calvary United Methodist Church in 1989. Text and images courtesy Calvary United Methodist Church.

NOTES

1. The Calvary Church archives contain several important sources for its building history: History of Calvary Methodist Church: 1895-1945 (Philadelphia, 1945); “Ninth Anniversary and Jubilee Rally Program: 1895-1904” (Philadelphia, March 9, 1904); “Program of Progress” (Philadelphia, 1957) and dedication program, November 20, 1907.

2. For the careers of John Dull and Robert Peterson see Sandra Tatman and Roger Moss, Dictionary of Philadelphia Architects (Philadelphia: The Athenaeum, 1986).

3. For examples of Carrell’s work see: Amityville School Long Island, American Architect and Building News XLIII (January-20, 1894); Sterling Arms, Pineapple Street, Brooklyn, American Architect and Building News LXIV (April 22, 1-899); and the Casa Alemada, 63rd and Columbus, Manhattan, American Architect and Building News XL (May 27, 1893). Also see the obituary in the American Architect and Building News CVIII (1915), p. 30. Gillespie’s career can be traced through New York city directories.

4. Gillespie and Carrel may have had other connections with Philadelphia. They built, for example, the Webb Mausoleum in Laurel Hill Cemetery. See the Architectural Record XLI (January 1917), pp. 72-73.

This report was researched and prepared by Michael Lewis of Clio Group, Inc. for Calvary United Methodist Church in 1989. Text and images courtesy Calvary United Methodist Church.

NOTES

1. The Calvary Church archives contain several important sources for its building history: History of Calvary Methodist Church: 1895-1945 (Philadelphia, 1945); “Ninth Anniversary and Jubilee Rally Program: 1895-1904” (Philadelphia, March 9, 1904); “Program of Progress” (Philadelphia, 1957) and dedication program, November 20, 1907.

2. For the careers of John Dull and Robert Peterson see Sandra Tatman and Roger Moss, Dictionary of Philadelphia Architects (Philadelphia: The Athenaeum, 1986).

3. For examples of Carrell’s work see: Amityville School Long Island, American Architect and Building News XLIII (January-20, 1894); Sterling Arms, Pineapple Street, Brooklyn, American Architect and Building News LXIV (April 22, 1-899); and the Casa Alemada, 63rd and Columbus, Manhattan, American Architect and Building News XL (May 27, 1893). Also see the obituary in the American Architect and Building News CVIII (1915), p. 30. Gillespie’s career can be traced through New York city directories.

4. Gillespie and Carrel may have had other connections with Philadelphia. They built, for example, the Webb Mausoleum in Laurel Hill Cemetery. See the Architectural Record XLI (January 1917), pp. 72-73.